Never give up. Never surrender.

By Sonya Mohamed, Nature Unplugged

If you’re like most of us, you have your phone with you 24 hours a day. It probably sleeps beside you on your nightstand, wishing you sweet dreams before you fall asleep and greeting you in the morning when you wake up with too many notifications and alerts. Our phones are glued to us and we’re usually plugged into a variety of devices every day for work, school, socializing and entertainment.

And, now, things are so intense! With social distancing, isolation, remote work, and school closures, we’re all turning to screens and technology to meet our needs and fill our time. It’s easy to throw in the towel and call it quits, and accept that the only way to survive this moment is to let technology take over. You certainly wouldn’t be alone if you did.

In fact, I read an article in the New York Times a couple of weeks ago titled Coronavirus Ended the Screen-Time Debate. Screens Won. I almost lost my mind just from reading the title. Did screen time all of a sudden become less problematic for our health and well-being just because we’re in the midst of a pandemic? Of course not. Were we all suddenly confronted with a new, very virtual way of living? Absolutely.

By default, there are things beyond our control that require us to use screens differently (and a bit more) right now. I’m not naive and I’m not a saint. Of course, you’ll be making concessions. I know I have, and I know I’ll continue to as we ride this out. But that’s different than throwing your hands up in the air and admitting defeat.

This is the precise moment to really start paying attention to your screen time and figure out how you can balance it out with nature and low- or no-tech activities.

As my home-girl Pema Chödrön said, “Nothing ever goes away until it has taught us what we need to learn.” Can you see the opportunity here? This pandemic has amplified our tech use and restricted our access to nature. If we can figure out how to find balance right now, we’ll have incredible habits and structures in place for when we ease back into normal.

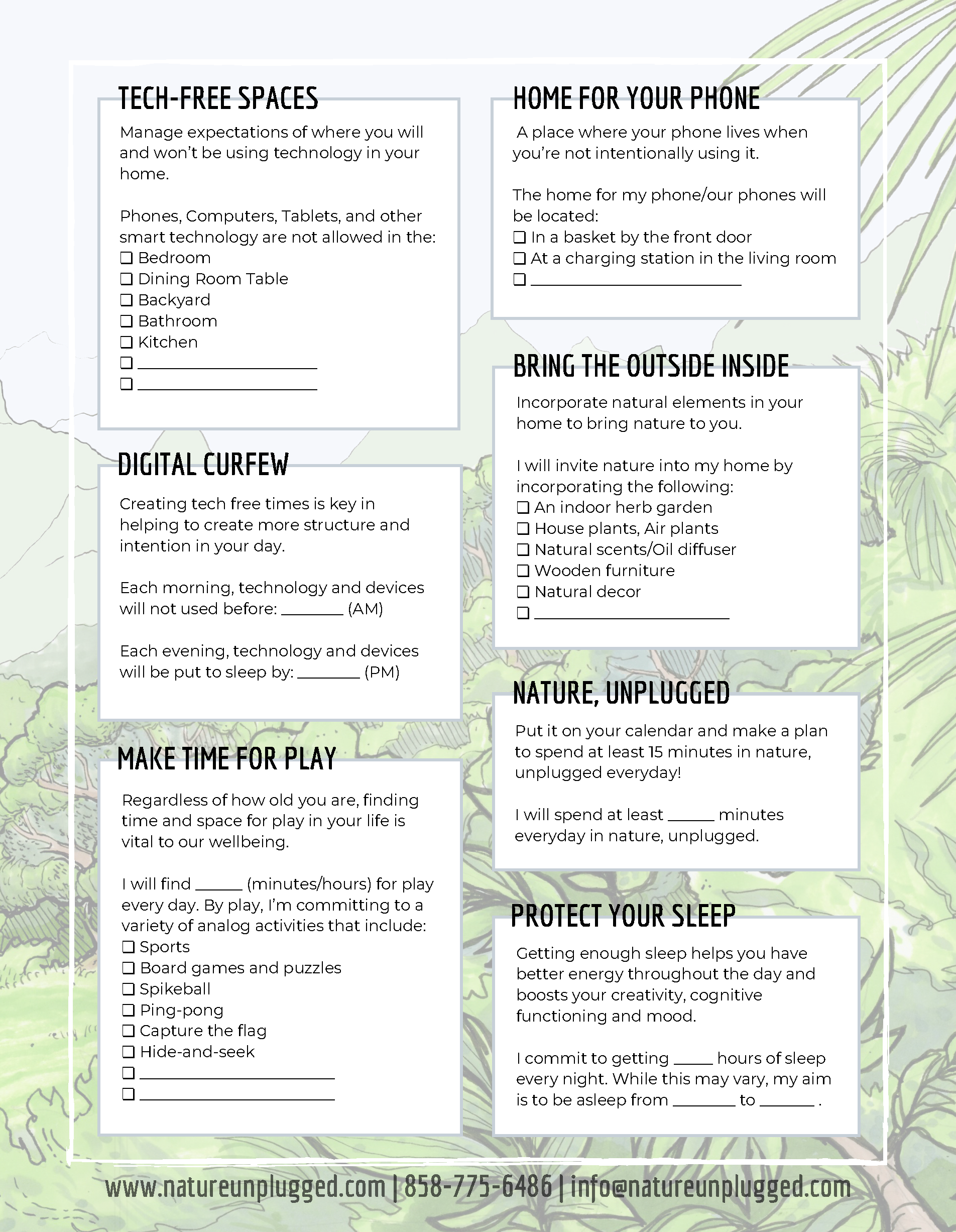

To help you get started right away, here is our quick-start guide to wellness in the digital age. It includes seven of our favorite tips and a mini-contract that promotes balanced living and healthy relationships with technology.

“Never give up. Never surrender.”

– From a movie I’m only moderately embarrassed to admit that I love, Galaxy Quest.

About Nature Unplugged:

Our work is all about inspiring wellness in the digital age. We help individuals, families, educators and organizations break free from the clutches of technology overuse, reconnect with nature and engage with life and work in a whole new way. Nature Unplugged is a member of The Hive.

Black, Jewish and Queer. These three identities weave the fabric of who I am, but it took a long time to believe that they could exist together.

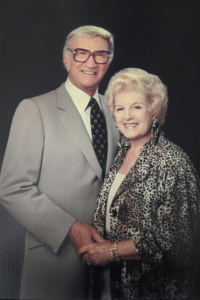

Black, Jewish and Queer. These three identities weave the fabric of who I am, but it took a long time to believe that they could exist together. Lee and Toni Leichtag established the Leichtag Foundation in 1991 following the sale of their business. Lee and Toni were lifelong entrepreneurs with a passion for innovation and for supporting talent. They believed that only with big risk comes big reward. Both born to families in poverty, Toni to a single mother, they strongly believed in helping those most in need and most vulnerable in our community. While they supported many causes, their strongest support was for young children and the elderly, two demographics who particularly lack voice in our society.

Lee and Toni Leichtag established the Leichtag Foundation in 1991 following the sale of their business. Lee and Toni were lifelong entrepreneurs with a passion for innovation and for supporting talent. They believed that only with big risk comes big reward. Both born to families in poverty, Toni to a single mother, they strongly believed in helping those most in need and most vulnerable in our community. While they supported many causes, their strongest support was for young children and the elderly, two demographics who particularly lack voice in our society. Lifelong Baltimoreans, Rabbi George and Alison Wielechowski and their sons, 11-year-old Lennon and 9-year-old Gideon, are more than pursuing the good life in Southern California. Having moved to San Diego more than three years ago, they are fulfilling a lifelong dream.

Lifelong Baltimoreans, Rabbi George and Alison Wielechowski and their sons, 11-year-old Lennon and 9-year-old Gideon, are more than pursuing the good life in Southern California. Having moved to San Diego more than three years ago, they are fulfilling a lifelong dream.

You would think that as the executive director of San Diego LGBT Pride, Fernando Zweifach López Jr., who uses the pronoun they, has done all the coming out they possibly can. A queer, non-binary individual who has worked for many years on civil rights issues, López also speaks openly and often about their father’s family, Mexican-American migrant workers who tilled the fields of rural California.

You would think that as the executive director of San Diego LGBT Pride, Fernando Zweifach López Jr., who uses the pronoun they, has done all the coming out they possibly can. A queer, non-binary individual who has worked for many years on civil rights issues, López also speaks openly and often about their father’s family, Mexican-American migrant workers who tilled the fields of rural California. Stacie and Jeff Cook understand commitment. They live it.

Stacie and Jeff Cook understand commitment. They live it.