Donor Stewardship: Follow-up that Fosters Loyalty

via Zoom CADid you know that most nonprofits lose nearly as many donors as they gain each year? Join us for this workshop to stop the churn! We’ll share tips for developing […]

Did you know that most nonprofits lose nearly as many donors as they gain each year? Join us for this workshop to stop the churn! We’ll share tips for developing […]

Join local colleagues in philanthropy for this informal, virtual time to check in with one another, ask questions, and get advice on fundraising matters.

Join us for a 4-session series as we gather virtually with our San Diego Jewish communal professionals, led by Chaya Gilboa. The sessions will be opportunities to learn together but […]

Join local colleagues in philanthropy for this informal, virtual time to check in with one another, ask questions, and get advice on fundraising matters.

Successfully securing corporate sponsors for your events and programs can boost your budget and staff capacity. Benefits also include attracting new audiences, increased visibility and added credibility. Advantages to companies […]

Join local colleagues in philanthropy for this informal, virtual time to check in with one another, ask questions, and get advice on fundraising matters.

Join local colleagues in philanthropy for this informal, virtual time to check in with one another, ask questions, and get advice on fundraising matters.

Join us for a 4-session series as we gather virtually with our San Diego Jewish communal professionals, led by Chaya Gilboa. The sessions will be opportunities to learn together but […]

Stories shape our organizations, our relationships with donors and constituents, and most importantly, our own self-perceptions. Through a Community-Centric Fundraising lens, we will explore how narratives we share, and the […]

In The ARTful Conversation, participants learn how to balance hearing another’s perspective while also communicating their own needs, gain a deeper understanding of how others perceive and process conflict, and […]

Black. White. Jewish. Christian. Male. Female. Curly hair. Straight hair. Every day, in every way, people make assumptions about others based on gender, affect, physical attributes, gestures, and accents. Shoshannah and Cedric Hart know a thing or two about this, as they have spent many years listening to what others think they know about them.

When the Arizona natives began dating more than 10 years ago-she was about to begin college at Arizona State University, he was finishing up there-they faced a barrage of questions from Cedric’s parents, devout Christians, about Shoshannah’s belief system.

“They asked me, ‘How do you celebrate Christmas? Why don’t you believe in Jesus?”‘ recalled Shoshannah, 28, who grew up in a strongly identified Reform Jewish home in Phoenix and attended a local Chabad synagogue, where she observed her Bat Mitzvah.

Jump ahead five years to their move to California, where Shoshannah, now a practicing attorney, went to law school, and Cedric, 32, found himself in the hot seat. The couple would be at a synagogue service or another Jewish gathering, and people would question whether Cedric was Jewish, since he is African American.

“It is kind of annoying,” Cedric, an elementary school physical education teacher, said, speaking in the present because questions of his Jewish identity still persist. “But I try to brush it off.”

Nevertheless, he conceded, the effect is alienating. “It kind of makes me feel pushed out.”

What both Harts would like people to know is that Cedric is every bit as Jewish as Shoshannah. He underwent conversion more than two years ago, after several years of serious study. He did so not because his then -fiancee asked him to-in fact, like traditional rabbis, she discouraged him until she was certain he was doing it for himself-but because he wanted to be Jewish like the children they planned to raise together.

Now the parents of a five-month-old son, Ezra, and three-year residents of San Diego, Shoshannah and Cedric find that living in North County affords them multiple opportunities to express themselves as Jews. Members of Congregation B’nai Tikvah in Carlsbad, they also participate in family programs at Cardiff’s Temple Solel, as well as many activities at The Hive and Coastal Roots Farm, including Great Outdoors Shabbat; Tu B’Av, a Jewish version of Valentine’s Day; and the Sukkot Harvest Festival. They said that they appreciate Leichtag Commons’ ability to attract San Diego Jews of all ages, colors, levels of observance, genders, and sexual orientations.

It is also why Shoshannah is drawn to Shalom Baby, a program run by San Diego’s Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center, which enables new parents and babies to meet each other. Through the group, she has become friendly with an LGBTQ mom and another participant married to a black man from Israel-a reminder, she said, that “there are Jews of many colors.”

Cedric added that he, too, is feeling the warm embrace of the San Diego Jewish community. For him, he said, it’s all about “joining in and talking to each other and learning.”

Local emergency room physician Dr. Chad Valderrama is in awe of his wife, Julie Avanzino, who, he says, remains as graceful as the professional ballet dancer she once was.

He particularly marvels how Julie, who danced with major companies in Pittsburgh, Denver, and San Diego, has seamlessly adopted Jewish traditions and practices, though she was not born Jewish.

“While creating a Jewish home is important to all of us,” said Chad, who is 36, “Julie takes the lead in organizing” for the holidays, such as Sukkot, Hanukkah, and Passover. “So even though she has not converted, she is just as Jewish as I am.”

For her part, Julie, also 36, said that she welcomes being part of the San Diego Jewish community and feels embraced by it. This sense of belonging is important to Julie, the daughter of two chemists, an Italian-American father and Chinese-American mother.

“My parents are agnostics/atheists,” said Julie, who grew up with no religious identity in the Silicon Valley. “On the one hand, it is fine. On the other, holidays had no meaning to me.”

The couple, parents to infant daughter Olivia, with another baby on the way, said that the Jewish calendar allows them to take pause to reflect on the importance of life, love, and family and to observe the passage of time.

“San Diego has allowed us a lot of opportunities to explore who we are.”

In very concrete ways, said Chad, the son of a Jewish mother and Spanish father who converted to Judaism, the San Diego Jewish community, of which he is a product, helped shape his Jewish identity.

Growing up in La Jolla, Chad, along with his family, attended nearby Congregation Beth Israel. While synagogue life was important, there were Jewish-sponsored activities that opened his eyes to tikkun olam, the idea the Jews have a solemn responsibility to repair the world. In high school, he and other Jewish teens participated in Operation Understanding, traveling by bus to the Deep South to learn more about the ways in which American Jews worked with African-Americans during the Civil Rights Movement. He also took part in the Aaron Price Fellowship Program, sponsored by Price Philanthropies in San Diego, which enables San Diego public high school students from diverse backgrounds to come together to build friendships and to take part in civic-oriented experiences that promote lifelong commitments to their communities.

“San Diego has allowed us a lot of opportunities to explore who we are,” said Chad.

While the Avanzino-Valderrama family is not affiliated with a local synagogue—they are shul shopping—they come to The Hive and Coastal Roots Farm for a host of activities. “Olivia loves the chickens,” said Julie.

Julie also stays connected locally to families she and Chad met during Honeymoon Israel, a program that brings newly married interfaith and Jewish couples together for meaningful experiences in Israel. With the friends she made on that trip, she continues to engage in mitzvah activities that support those in need.

“These are all ways that reflect our values,” Chad said.

Unlike her parents, a retired judge and estate planning attorney, and her brother, a civil rights lawyer who worked in the Obama Administration, Jessica Pressman does not use the law to effect the changes she believes are needed in her community. But the 44-year-old San Diego native, a professor of English at San Diego State University, did learn early on to call out injustices when she saw them and to strive to make the world a better place.

In San Diego, and, in particular, its Jewish community, Jessica and her husband of 17 years, Brad Lupien, a non-Jewish social-worker-and-teacher-turned-entrepreneur, are trying to teach their two Jewish-raised children, 12-year-old Jonah and 10-year-old Sydney, the lessons of tikkun olam—repairing the world—through example.

On the local level, she and another Jewish parent at her children’s school in North County spoke up when administrators planned a major event to take place on Yom Kippur. They were successful in changing the event date.

Jessica was less successful, she said, when she tried to organize friends to go with her to a local protest against racism and anti-Semitism after the white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“The response I got was, ‘I am going to focus inward, and keep my energy focused on family and all that is right in our magical little community.’” she recalled. “‘The magical little community’ set me off. Are you kidding me? I grew up here. You have no idea.”

Thirty years ago, Jessica said, prejudice was quite overt in San Diego. Swastikas appeared after her brother ran for a student government office at Torrey Pines High School, and she had to explain to friends why the expression “Don’t bagel me,” a modern-day version of “Don’t Jew me,” was offensive.

“‘The magical little community’ set me off. Are you kidding me? I grew up here. You have no idea.”

Jessica said that the climate is ripe in San Diego, which she says has come a long way since the days of swastikas, for more education and positive change. And she sees The Hive and Coastal Roots Farm as incubators for such progress. When she couldn’t get friends to attend the anti-prejudice protest with her, she contacted Leichtag Foundation, which organized a program on Judaism and race relations.

She is also grateful for the opportunities the San Diego Jewish community affords her and her family to educate themselves. Soon after she and Brad, 43, returned from the East Coast, where Jessica was teaching at Yale, they participated in a Jewish Community Foundation-supported Jewish Giving Circle to learn more about tzedakah and Jewish philanthropy.

“It was foundational,” she said, “in how to give and to make friends in the Jewish community.

“There are a lot of ways in,” Jessica continued, referring to the entry points of Jewish engagement in San Diego, and she and Brad and their kids are relishing the chance to discover and access as many of them as possible.

Stacie and Jeff Cook understand commitment. They live it.

Stacie and Jeff Cook understand commitment. They live it.

A Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy, Dr. Jeff Cook, 37, is also an emergency room physician who has cared for injured and sick military soldiers in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and, more recently, in Kuwait, where he was deployed last year. Like all military families, he and Stacie, an obstetrician/gynecologist, are accustomed to constant moves when the Navy calls him up: They most recently lived in Yokosuka, Japan, and, before that, Jacksonville, Florida. But now that they have two children, 3-year-old Ari and 1-year-old Olive, they are happy to be settled, at least for the next couple of years, in North County, where they are committed to creating a Jewish home for their children.

Their commitment is such that Stacie, 38, who grew up Episcopalian in Upstate New York, drives 20 miles each way through the county’s back roads to transport Ari to Temple Solel’s preschool program in Cardiff-by-the-Sea. Impressed by her interest and involvement in her children’s Jewish education, the synagogue’s preschool administration appointed her co-chair of the PTA.

Stacie said that her desire to help her children lead Jewish lives and to support the local Jewish community any way she can is tempered by her own concerns that she might

“do something wrong,” be it go against a traditional Jewish practice or misspeak a Jewish prayer. But, she acknowledged, no one in the community has ever corrected her and, in fact, everyone has been unfailingly supportive of her efforts.

“I feel very welcomed by the community,” said Stacie, who has taken a leave from medicine to raise the family.

“Judaism can center you and give you a community.”

Jeff grew up in a Conservative Jewish home in suburban Atlanta, the son of a mother who is active in the Jewish community and a Sephardic father. Over the 15 years in the military, he has worked in earnest to maintain a strong Jewish practice. He attended a Passover Seder in Afghanistan, High Holiday services in Kuwait, and, on occasion, Shabbat services on bases overseas. He and Stacie also were part of a small, tightknit Jewish community of military families in Japan.

Here, in North County, with few Jewish families in their immediate area, they often find themselves on weekends en route to military friends’ homes for Shabbat and other holidays.

Contrary to the notion that few Jews serve in the military, the “proportion of Jews in the service is probably the same as the population as a whole,” Jeff said, noting that his commanding officer at the Naval Medical Center in San Diego is also Jewish.

The local Jewish community, both civilian and military, has been a grounding force for her constantly moving family, said Stacie, who has attended programs at The Hive and Coastal Roots Farm and is considering conversion to Judaism.

“You can lose control of your life [because] you’re at the whim of military assignments,” she said. “Judaism can center you and give you a community.”

Black, Jewish and Queer. These three identities weave the fabric of who I am, but it took a long time to believe that they could exist together.

Black, Jewish and Queer. These three identities weave the fabric of who I am, but it took a long time to believe that they could exist together.

The idea of “belonging” was foreign to me for much of my life. I was aligned with three communities that historically faced oppression in society, and there was no type of representation I could see for people like me. Questions of my existence as a Black Jew, and the implications that came with being Black and Queer would overwhelm me.

Because of this, I watered down my Jewish identity through my teenage years. I could only focus on discovering myself through my other two identities, which was hard enough. When I entered college, I was invited to join Hillel, which piqued my interest in Judaism. I attended all through my college years, finding community in weekly Shabbats, learning about Israel, and expressing my Jewishness more.

Slowly but surely, my Jewish expression began to exist on the same plane as my Blackness and Queerness. I could fit them all at the table instead of checking them at the door. I experienced more acceptance of myself, and from other people, and I began to feel more included in all the communities I represented.

Still, feeling included didn’t mean that I felt like I belonged. Fast forward to 2019 and I’m at a conference listening to UC Berkeley’s john a. powell speak to us about “belonging” as a result of co-creation. He remarked that “inclusion” implied that one must extend an invitation to their space, thus creating an imbalanced power dynamic. “Belonging” relates to the idea that a space is co-created with others, ensuring that everyone has equal and equitable access because they belong there.

My work with the Leichtag Foundation and The Hive has led me on an exploration of “belonging,” not just for myself, but for anyone who, like me, felt that they didn’t belong in any space. This is the reason behind This is San Diego Jewry. I want to show this unique, vibrant community that we all belong here.

San Diego has been the space where I’ve truly dived into my Jewishness and discovered what I love about it, and how I want to wield it in my life. Our closeness to nature motivates me to weave in Jewish values of agriculture at home. The values of tzedakah and Tikkun Olam align with and inspire my own views of justice and liberation. The creative ways that we express our Jewishness as a community excite me for how I’ll apply these lessons to wherever I go in the future.

I realize now that I belong anywhere that I want to be. I belong where I can help others experience belonging. I belong where I, a Black-and-Jewish-and-Queer person, can create work like this that represents the true expansiveness of our San Diego Jewish expression. And we all belong here because we are the tapestry of this community.

Thank you for weaving it with us.

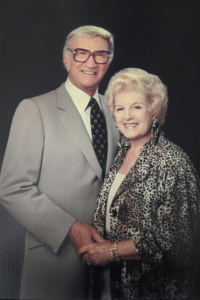

Lee and Toni Leichtag established the Leichtag Foundation in 1991 following the sale of their business. Lee and Toni were lifelong entrepreneurs with a passion for innovation and for supporting talent. They believed that only with big risk comes big reward. Both born to families in poverty, Toni to a single mother, they strongly believed in helping those most in need and most vulnerable in our community. While they supported many causes, their strongest support was for young children and the elderly, two demographics who particularly lack voice in our society.

Lee and Toni Leichtag established the Leichtag Foundation in 1991 following the sale of their business. Lee and Toni were lifelong entrepreneurs with a passion for innovation and for supporting talent. They believed that only with big risk comes big reward. Both born to families in poverty, Toni to a single mother, they strongly believed in helping those most in need and most vulnerable in our community. While they supported many causes, their strongest support was for young children and the elderly, two demographics who particularly lack voice in our society.

“G-d has been good to us, we want to return the favor.”

Lee and Toni were partners in every sense. They were proud parents of Joli Ann Leichtag, of blessed memory, and enjoyed being grandparents. When asked about his most significant

accomplishment in life, Lee said, “My marriage to Toni.” This testament of their partnership and their commitment to family and community are the foundation of the legacy the Leichtag Foundation strives to honor.

Lifelong Baltimoreans, Rabbi George and Alison Wielechowski and their sons, 11-year-old Lennon and 9-year-old Gideon, are more than pursuing the good life in Southern California. Having moved to San Diego more than three years ago, they are fulfilling a lifelong dream.

Lifelong Baltimoreans, Rabbi George and Alison Wielechowski and their sons, 11-year-old Lennon and 9-year-old Gideon, are more than pursuing the good life in Southern California. Having moved to San Diego more than three years ago, they are fulfilling a lifelong dream.

The pretext for their journey west was family: Alison’s sister and mother already lived here. But for George, 42, an entrepreneur as well as a clergyman, the region’s startup climate was as alluring as the physical environment in which to practice his and Alison’s form of Judaism.

Most recently, George was the executive director of the San Diego-based Open Dor Project, which encourages and funds the development of new and emerging spiritual models of Jewish life around the country.

As gratifying as Open Dor has been, he and Alison, 40, are also enthused by their creation of a havurah friend group of 10 mostly interfaith families that, thanks to San Diego’s famously temperate climes, meets mostly at parks, trails, and beaches for monthly Shabbat and other observances.

“For Shavuot, we took a hike mimicking the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai,” said George, who was ordained at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. “We talked about the meaning of revelations.”

San Diego’s cultural and natural climates give rise to “meaningful opportunities” for Jews to express themselves in a seemingly infinite number of ways.

Al fresco Judaism, San Diego style, is thousands of miles from the lives they led in Maryland. George grew up in Section 8 public housing with his Evangelical Christian single mother, a domestic from Guatemala, who, he said, “saved up all her money to buy the smallest house in the nicest neighborhood that she could afford,” which also happened to be the nexus of Jewish life in the northwestern part of Baltimore County. As he spent time with Jewish classmates and friends and their families, he said, he came to love their history, culture, and traditions. He converted to Judaism 16 years ago.

Alison was raised in a neighboring part of Baltimore that was also predominantly Jewish.

Her father was an executive director of a Conservative synagogue, and she led a fairly traditional Jewish life. Active participation in a Jewish student association at college led to a long career in the Jewish world—as director of Goucher College Hillel and, most recently, as director of development at Krieger Schechter Day school.

The Wielechowskis said that San Diego is also giving their sons an appreciation for experiencing Judaism and nature concurrently. As Lennon begins preparing for his Bar Mitzvah, he is toying with the idea of incorporating into his ceremony a serious study of Jewish values and climate change. “Only in San Diego,” one might say.

Or, as George said, San Diego’s cultural and natural climates give rise to “meaningful opportunities” for Jews to express themselves in a seemingly infinite number of ways. The time for Jewish leadership to facilitate such is expression is “ripe,” he said.

Change came rapidly to Debbie Macdonald as she approached the half-century mark in the late 1990s.

First, seemingly out of the blue, the younger of her two sons, Josh, announced that he wanted to study for a bar mitzvah.

“This was a big surprise,” said Debbie, now a 72-year-old retired nonprofit administrator who, as a child, had attended a Conservative synagogue in San Diego with her family, but had become distanced from organized religion once she went away to college and graduate school.

“My husband at the time was not Jewish,” she said. “We did celebrate major Jewish holidays with my extended family, but I was not interested in joining a temple. I tried to ignore Josh’s requests because I did not think he would stick with it. But he continued to ask me to study for his bar mitzvah.”

So the Macdonald family joined San Diego’s Temple Emanu-El, which is where Debbie experienced another surprise.

“I got to know the rabbi there at the time, and I realized that Judaism could be very different than it had been when I was growing up,” she said.

So different, in fact, that Debbie wanted to have an adult bat mitzvah, and she began preparing for it soon after Josh had completed his religious studies.

“I realized that Judaism could be very different than it had been when I was growing up.”

A couple of years later, Debbie announced another major life change.

“I went to see the rabbi, and I told him two things,” she recounted. “First, I told him that I was getting a divorce. The second thing I told him was that I’m gay, and that I’m in love with a woman. He was happy for me and asked, “Is she Jewish?’”

That woman, Nancy Kossan, now 67, a retired academic and university administrator, is not Jewish. She was raised in a Protestant denomination. Describing herself now as “a-

religious,” she said that she enjoys the social action/social justice aspects of Reform Judaism.

Both women, who have been together for 19 years and were married in 2008, have found a welcoming home at Emanu-El. Debbie, who has served on the congregation’s board for many years, was its first lesbian president. She and Nancy attend Shabbat services at least once a month, and have taken a number of classes there over the years, including an introduction to Judaism and Hebrew Bible courses. Both also appreciate the temple’s emphasis on civil and human rights, with Debbie noting that Emanu-El was the first among the half dozen synagogues that now march in San Diego’s LGBTQ Pride parade.

While synagogue life takes up a good portion of their lives, Debbie and Nancy, who live in the city’s Pacific Beach neighborhood, have found time for involvement in other Jewish groups, including a havurah. Always interested in child welfare, Debbie has also donated time and resources to Jewish Family Service of San Diego.

If you had asked her 30 years ago whether she would be active in a synagogue and engaged in the Jewish community, “I would have said, ‘Not in a million years,’” Debbie reflected.

When Katie Mendelson, who now goes by Chaya Ertel, was a teen, she loved cruising Los Angeles’ Hollywood Boulevard at midnight with friends, seeing what mischief she could whip up.

“I was a free spirit,” recalled the 41-year-old mother of five. Chaya is now a partner, with husband Rabbi Eric Ertel, known as Shmuely, in an 11-year old venture called San Diego Jewish Experience, which offers religious, cultural, and educational opportunities to hundreds of local college students, most of whom are at University of California, San Diego.

Chaya may no longer be “a free spirit,” but she retains a huge sense of fun … plus a deep understanding of young people’s hunger to achieve meaning in the world. That’s a desire of which she has first-hand knowledge.

After high school, Chaya spent a year in Israel as part of a Conservative Jewish post-secondary program. But she quickly fell in with a group of more observant Jews and determined that she wanted to lead an Orthodox life. Alarmed by what they saw as her turn to the religious right, the leaders of Chaya’s program summoned her father to Israel to “deprogram” her. Instead, he gave his blessing. He could see, Chaya said, that Orthodox Judaism had given her the “clarity” that she had sought.

Chaya and Shmuely, 42, who grew up in New Jersey to a family that subsequently embraced Orthodox Judaism, met through a matchmaker in Israel, where they continued their studies and Shmuely was ordained. The courtyard of their La Jolla home, on the edge of the UC San Diego campus, is ground zero for the host of Jewish experiences occurring seemingly round the clock: study groups, drop-in rap sessions, challah baking demonstrations, and Shabbat and holiday dinners. Shmuely says that he works with about 250 students annually, some of whom he escorts to Israel on yearly Birthright trips, and Chaya estimates she prepares 10,000 meals each year.

“[W]e don’t hand G-d a shopping list of our needs and wants. It is about a relationship.”

While the Ertels see the students, most of whom are from interfaith families, as extensions of their own family—Shmuely is impressed by their “perseverance and commitment” to acquire a stronger identity, Chaya with their struggles with faith, even in the face of “life’s painful, messy realities”—they also nurture their own San Diego Jewish experiences. They are members of La Jolla’s Congregation Adat Yeshurun, and

their eldest daughter, now in college, was the first Orthodox teen to participate in the Jewish Community Foundation of San Diego’s program to teach young people about Jewish philanthropy. Avid runners, Shmuely and Chaya also take part in La Jolla’s annual 5K.

But San Diego Jewish Experience is never far from their minds or hearts, because the students’ challenges are their own.

Thinking back to a young woman she mentored, Chaya said, “She was young when her mother passed away from cancer, and she came to shul the night of her mother’s yahrtzeit, maybe to doven, maybe just to feel close to G-d. Not sure. But I have to believe as a little girl, she prayed her mother would get well. And the answer was obviously no. And yet there she was, reaching out. She taught me the definition of spiritual maturity and grit–that we don’t hand G-d a shopping list of our needs and wants. It is about a relationship. Sometimes there are tremendous disappointments, and we won’t always know why, but … she was there for the long haul.”

More than 40 years ago, Ruth Platner did something rare for the times. She divorced her husband of almost 30 years, packed her bags, and moved from Wausau, Wisconsin, a small city in the northern part of the state, to San Diego’s North County, where she embarked on an entirely new life.

With her daughters grown and involved in their own families and careers, Ruth, unencumbered, thrived. A painter and sculptor, she devoted her life to her artwork and the enhancement of the local art scene. She taught craft skills to developmentally disabled young adults, helped set up an art school at the Oceanside Museum of Art, and earned a master’s degree in educational technology.

“She was pretty gutsy,” said her eldest daughter, Mimi Miller, an acupuncturist who lives in a San Diego beachfront community about 15 miles south of her mother.

At 92, Ruth still is.

She continues to live in the condominium she has owned for decades and to enjoy a rich life. Though she no longer makes art, she still displays it—most recently, at The Hive’s Farmhouse Gallery, where, this past May, she had a one-woman exhibit of her acrylic paintings. The show coincided with the observance of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Ruth knows something of the Holocaust, too.

“We are no longer traditional Jews, [but I feel] a deep connection to the Jewish part of myself.”

Born in Hamburg, Germany, Ruth was a young girl when the Nazis rose to power. While family and friends fled the country or were shipped off to concentration and death camps, Ruth, her Jewish mother, and non-Jewish father kept a low profile in an attic apartment that her father had secured for them. They lived there throughout World War II, in constant fear of being discovered and deported. During that time, a number of her immediate family members were killed.

After the war, Ruth resumed her studies at the Hamburg Art Institute. “When life hands you mud (in this case, from the bomb crater), make a sculpture,” she recalled in “War and Pieces: Healing Through Life’s Struggles,” her 2015 memoir. She also met and married a fellow Holocaust survivor, Fred Platner, the man she later divorced but with whom she stayed friendly. A pillar in Wausau’s tiny Jewish community, Fred died in 1988. Ruth cared for him at the end of his life.

As she developed her own style in the United States, Ruth segued from sculpture to painting, often focusing on Jewish subjects, such as the Kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism, and members of her family. While becoming active in San Diego’s Jewish Renewal movement and attending services at the North County Elijah Minyan, she also became affiliated with a local Buddhist group.

“She will say that she’s a JewBu,” Mimi said, explaining that her mother has incorporated the teachings and practices of both faiths into her life and personal philosophy.

The free, open spirit that Ruth has come to embody is reflected in her family members—her three daughters, five grandchildren and one great-grandchild—who include people of color and of various faith traditions.

“We are no longer traditional Jews,” said Mimi, who nonetheless feels “a deep connection to the Jewish part of myself. When I participate in the traditions, I appreciate the richness.”

Eve Rosenberg is, to use the Yiddish she so loves, a shtarke, a strong, sturdy, and resilient soul.

At 105, Eve has the distinction of being the oldest resident of the Seacrest Village Retirement Communities in Encinitas. But after 11 years at Seacrest, whose origins date back 75 years to the San Diego Hebrew Home, Eve is also famous among residents and staff for her wit and keen intellect. In short, her community loves her. And she is delighted to return the compliment.

“Everything about Seacrest is wonderful,” Eve kvelled, or gushed with the pride of a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother, all of which she is. “It is a piece of paradise. Everything is done with such good taste.”

Paradise is not the environment in which Eve spent most of her life. Born in Detroit to Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Eve, along with her parents and sister, moved to New York during the height of the Great Depression in the early 1930s to find work. College was out of the question, as there was no money for it, and she took whatever jobs she could find to help support her family. She was fortunate, at one point, she said, to work at the New York Public Library, “because I love books.”

Eve was also fortunate, at another job, to meet the man who would become her husband: Murray Rosenberg.

“Life pitches you balls, and you have to catch them.”

“I was working at a very interesting shop on Fifth Avenue when he walked in,” Eve said, recounting how they met. “He was dashing. He was wearing his uniform [since he was a solder during World War II].”

The couple had two sons after the war, the younger of whom, Jonathan, 68, is a longtime San Diego resident. Sadly, Murray, exposed to yellow fever during his military service in the Philippines, died prematurely, leaving Eve a widow for more than four decades.

Through many hardships, though, Eve has striven to take a philosophical approach. “Life pitches you balls,” she said, “and you have to catch them.”

Eve would have stayed in New York had its harsh winters not exacerbated her longtime battles with bronchitis. At Seacrest, close to Jonathan and his family, she participates in almost every discussion and study activity, relishing the classes with Seacrest’s rabbi. Though she herself is not observant, she said, “I have a neshama, a Jewish soul.”

Like many San Diegans, Eve enjoys the great outdoors. “I love walking every day among the interesting trees at Seacrest,” she said.

Eve said that she is reminded of something her mother said to her so many decades ago: “In life there are a lot of bridges … Whatever way, you have to cross the bridge.”

She concluded, “Crossing the bridge to Seacrest was the one of the best choices I’ve made.”

Though they were both brought up in strongly identified Jewish families, Yaniv and Liron Scherson have, in a very real sense, a mixed marriage. Their union is a blending of cultures—on Yaniv’s side, Ashkenazi and Latin American; on Liron’s, Mizrahi, Sephardic, and Israeli—making their family a diaspora of world Jewry.

Cultural differences aside, the North County couple form a united front on two significant issues: passing along strong Jewish identities to their two sons, 7-year-old Noam and 4-year-old Amit, and ensuring the continuation of a vibrant Israel.

The son a Chilean Jewish father and Mexican Jewish mother and grandson of Polish and Lithuanian immigrants who fled to Central and South America as the Nazis rose to power, Yaniv, 35, a Berkeley- and Stanford-educated innovator in renewable energy sources, has strong family connections to Israel himself. His parents, also scientists, earned their doctorates from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, and he met Liron, 38, an Israeli native, on a trip to the Jewish state.

Liron, a social worker who has worked with at-risk youth and special needs children, grew up in the city of Ramat Gan, the daughter of a father from Casablanca, Morocco, and a mother of Yemeni ancestry. Her parents’ marriage represented a unique and uncommon commingling of the two cultures at that time.

The Schersons decided five years ago to move from the San Francisco Bay Area to San Diego’s North County.

“I think that the Jewish community here is amazing,” said Liron. Though it is smaller than the Bay Area’s, she said, its size “creates intimacy.”

“People are happy and grateful to live here … and they want to make connections [with others].

In fact, noted Yaniv, since they moved to North County, they have met several other Israeli families in their own community and have formed core friendships with all of them. That has allowed them to remain connected to Israel, which they visit yearly.

At the same time, the Schersons love the diversity of San Diego’s Jewish community, which, Yaniv noted, includes significant numbers of immigrants from four corners of the world: South Africa and the former Soviet Union, in addition to Mexico and Israel.

The Schersons said that the rise of anti-Semitism in the United States—the recent shootings at the Chabad synagogue in Poway and appearance of swastikas in Carmel Valley rattled them deeply—is a sober reminder of the plight their ancestors faced to maintain their religious and cultural identities and of the responsibility they feel in continuing Jewish traditions.

Yet they are very grateful to live in a community that is integrated and welcoming and appreciate the opportunity to participate in and contribute to North County San Diego’s Jewish culture.

“People are happy and grateful to live here,” Liron said, and “they want to make connections [with others].”

Growing up in suburban Sacramento, the son of a father who became a born-again Christian and an Asian American mother who is half Japanese and half Filipina, Kyle Young, 33, had little contact with the Jewish community. In fact, he said, many of his classmates were Mormon.

But Kyle, who has lived in San Diego for nine years, finds himself immersed in the local Jewish community, both professionally and personally. He has been a marketing manager at the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center in La Jolla for almost two years, and he has shared his life for more than eight years with a Jewish man, Ben Winnick, 43, an Orange County native who is a database administrator at the San Diego Metropolitan Transit System. The two, who live in the Clairemont neighborhood of San Diego, will be married in March 2021, their 10th anniversary. They met singing together with the San Diego Gay Men’s Chorus.

Since they became a couple, and particularly since he has worked at the JCC, Kyle has become a fast student of Jewish history, culture, and tradition, though he considers himself religion-less and has no thoughts of adopting a faith-based tradition. For him, it is “all about family, community, and food rather than a relationship with God,” he said. “We go to Ben’s parents for Hanukkah and Passover,” and they occasionally make or go to Shabbat

dinner with friends.

“It’s all about seeing people where they’re at rather than where you want them to be.”

Ben, who came to San Diego in 2001, following graduate school at the University of Pittsburgh, is a strongly identified LGBTQ Jew. Although his family was heavily involved in a synagogue in his hometown of Anaheim, he is not a member of a local synagogue. Nevertheless, he appreciates his congregational options in San Diego and environs, having spent High Holidays at a number of shuls over the years, including Temple Emanu-El. He also takes pride in the local Jewish community’s visibility at the San Diego Pride Parade, noting that six or seven synagogues regularly march.

Kyle echoes Ben’s impressions of a San Diego Jewish community that is warm and embracing of a diverse Jewish community. Speaking of his workplace, he said, “Whether our members and guests are Conservative or Reform or Orthodox, or are part of an interfaith family—as I have found many Jewish people my age are—or in an interfaith relationship, the community center is welcoming, open, and receptive.”

Ben and Kyle and their families have all chosen to abide by that open-door policy. They put up a tree for Christmas, and Kyle’s mother crafts gifts for Ben’s family for Hanukkah.

“It’s all about seeing people where they’re at rather than where you want them to be,” said Kyle.

You would think that as the executive director of San Diego LGBT Pride, Fernando Zweifach López Jr., who uses the pronoun they, has done all the coming out they possibly can. A queer, non-binary individual who has worked for many years on civil rights issues, López also speaks openly and often about their father’s family, Mexican-American migrant workers who tilled the fields of rural California.

You would think that as the executive director of San Diego LGBT Pride, Fernando Zweifach López Jr., who uses the pronoun they, has done all the coming out they possibly can. A queer, non-binary individual who has worked for many years on civil rights issues, López also speaks openly and often about their father’s family, Mexican-American migrant workers who tilled the fields of rural California.

But after the recent Poway synagogue shooting, in which a gunman killed a worshiper and seriously maimed several others, López, 37, publicly reminded their community about another layer of their identity. In a mass email to SD Pride’s friends and supporters, with the subject line “I Am Jewish,” they wrote about their mother’s parents, Orthodox Jews from Russia and Austria.

While their Jewish coming out message—a call for greater tolerance and understanding among all oppressed minorities—was warmly embraced by most, López said, they also received quite a bit of hate mail. “More than ever before,” they added.

Rather than despairing about another example of rising anti-Semitism in this country, López remains dogged in their determination to counter bigotry head-on. After all, they said, they’ve been doing exactly that since they were a young child in the Imperial Valley.

“Observing Hanukkah keeps me grounded in my heritage and it reminds me of my grandparents’ stories.”

“Growing up, I was told, ‘You’re Jewish, you’re an immigrant. You’re going to face anti-Semitism and xenophobia,’” López said, explaining how they developed resilience.

López needed to call upon this inner strength when they realized, at an early age, that they were somehow different from most other kids.

“The bullying and harassment never stopped,” they said, once their peers saw that López was different, too.

Rejected by their family for their sexual orientation, López couch-surfed at friends’ homes for a year or so before moving to San Diego for work and college. They lived in a car for a while, survived several suicide attempts, and met a Jewish man, with whom

they had a seven-year relationship. Both became outspoken proponents of marriage equality, and López eventually went to work for one of the largest marriage equality advocacy groups before coming to SD Pride, where, in addition to running the annual Pride parade and festival, they develop a host of harm-reduction and anti-discrimination programs. They also founded an interfaith department that works with sympathetic religious groups locally to advance LGBTQ interests. Many of the faith-based groups are Jewish, which gratifies López immensely.

While not an observant Jew, López celebrates Hanukkah, lighting the menorah and saying the prayers. “It keeps me grounded in my heritage,” they said, “and it reminds me of my grandparents’ stories.”

López is also heartened by a full rapprochement with their father, “now one of my best friends and dearest advocates,” they said.

“It took 20 years,” they continued, “but we are now taking our first vacation together.”

Be the first to read the latest about Leichtag Foundation’s grantmaking and activites!