Jerusalem: Where Everyone Seeks to Hold On and Let Go

In January, we reflected on seven milestones and lessons from the last shmita cycle as we also look forward to the next. This third of seven reflections explains the Jerusalem Model’s creation and purpose through a lens of shmita.

My father has traveled by bus to shuk Mahane Yehuda in Jerusalem every Friday for fifty years. He has neither a driver’s license nor a shopping cart. He buys only what he can carry by hand. When my family lived in San Diego, I told him that the size of our hauls from the grocery store tripled because we could drive—and the amount of food we later threw away tripled as well. I could hear him smile through the telephone. When you don’t have to carry groceries home on the bus, you buy what you see, not what you need.

Recently I taught a class about shmita. The owner of a field, according to the Mishnah, is commanded to relinquish ownership during the shmita year to enable any passersby to enter the property and eat as much food as they need. The most interesting reflection from the conversation was: the practice of letting go is no less important for the person entering the field than it is for the owner. You can take as much as you want, but you must restrain that urge. You must take only what you need at that moment and not “a single apple more.” As my father told me, “Whatever doesn’t fit into my grocery bags, I clearly don’t need.”

During shmita, we let our environments grow naturally. We relinquish our almost obsessive need to influence the way things develop. We learn that not everything depends on us, and that there is value in release. After six years of building, the shmita year wants us to recognize the tension between our human desire to dominate and the desire to let go, set free. The delicate balance of shared ownership and taking just what we need.

Ownership is important. When we feel like something is “ours,” we are willing to work for it. Belongings foster responsibility—but is it possible to create responsibility without ownership? Our work here in Jerusalem attempts to maintain—and work with—these tensions.

Everyone wants to own Jerusalem. Any time someone visits Jerusalem, they can feel the quiet tremors underlying the everyday, whispering: Who owns this space? Who is the owner? Who is the guest?

In 2016, building on years of learning, granting and engaging grassroots Jerusalem leaders on an individual basis, Leichtag Foundation convened social activists who are working for a resilient Jerusalem to build on the energy of the city’s diversity, complexity, and passion. Out of a series of gatherings emerged the Jerusalem Model, a coalition of more than 200 bottom-up influencers and social entrepreneurs from all parts of Jerusalem who are working toward a better future for all the city’s diverse inhabitants. The Model’s vision is to catalyze a new generation of activists and urban leadership that sees success and prosperity of all populations living in Jerusalem as the key to the success of the city.

– Photos from the Jerusalem Model convenings

The shmita year has, in some sense, become the Model’s North Star. Is it possible to create a space, to provide tools and resources for blazing a path forward without forsaking individual and group identities? We want to enable initiatives to blossom and grow as they see fit, without dictating what they should do. Is it possible to build a community that will agree to leave everything we “know” about each other at the door, making room for a simple human encounter—an encounter between Jerusalemites?

Each time we enter the Jerusalem Model community, we necessarily ask: how is it possible to create a “shmita year” space with neither owners nor guests? How is it possible to create a space where everyone feels accepted? Which walls must we tear down so that everyone can “enter the field and take the fruit”? How do we release our incessant need to know it all?

These questions underlie almost every activity we lead in Jerusalem. How can we create a sense of responsibility without ownership? How is it possible—as it is in the shmita year—to recognize that the land and the space do not belong to some specific sector, while instilling a sense of responsibility for the entire space? It is possible to open both the hand and the heart, agreeing to relinquish all our fears about those who look different from us? In a city like Jerusalem, this sometimes seems like an unreasonable occurrence, but shmita comes once every seven years just to remind us that it is possible.

by Chaya Gilboa, Executive Director of Jerusalem Philanthropic Initiatives

by Chaya Gilboa, Executive Director of Jerusalem Philanthropic Initiatives

Black, Jewish and Queer. These three identities weave the fabric of who I am, but it took a long time to believe that they could exist together.

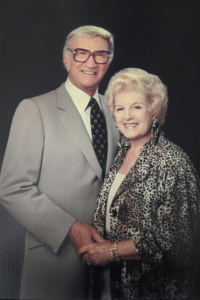

Black, Jewish and Queer. These three identities weave the fabric of who I am, but it took a long time to believe that they could exist together. Lee and Toni Leichtag established the Leichtag Foundation in 1991 following the sale of their business. Lee and Toni were lifelong entrepreneurs with a passion for innovation and for supporting talent. They believed that only with big risk comes big reward. Both born to families in poverty, Toni to a single mother, they strongly believed in helping those most in need and most vulnerable in our community. While they supported many causes, their strongest support was for young children and the elderly, two demographics who particularly lack voice in our society.

Lee and Toni Leichtag established the Leichtag Foundation in 1991 following the sale of their business. Lee and Toni were lifelong entrepreneurs with a passion for innovation and for supporting talent. They believed that only with big risk comes big reward. Both born to families in poverty, Toni to a single mother, they strongly believed in helping those most in need and most vulnerable in our community. While they supported many causes, their strongest support was for young children and the elderly, two demographics who particularly lack voice in our society. Lifelong Baltimoreans, Rabbi George and Alison Wielechowski and their sons, 11-year-old Lennon and 9-year-old Gideon, are more than pursuing the good life in Southern California. Having moved to San Diego more than three years ago, they are fulfilling a lifelong dream.

Lifelong Baltimoreans, Rabbi George and Alison Wielechowski and their sons, 11-year-old Lennon and 9-year-old Gideon, are more than pursuing the good life in Southern California. Having moved to San Diego more than three years ago, they are fulfilling a lifelong dream.

You would think that as the executive director of San Diego LGBT Pride, Fernando Zweifach López Jr., who uses the pronoun they, has done all the coming out they possibly can. A queer, non-binary individual who has worked for many years on civil rights issues, López also speaks openly and often about their father’s family, Mexican-American migrant workers who tilled the fields of rural California.

You would think that as the executive director of San Diego LGBT Pride, Fernando Zweifach López Jr., who uses the pronoun they, has done all the coming out they possibly can. A queer, non-binary individual who has worked for many years on civil rights issues, López also speaks openly and often about their father’s family, Mexican-American migrant workers who tilled the fields of rural California. Stacie and Jeff Cook understand commitment. They live it.

Stacie and Jeff Cook understand commitment. They live it.